Water is essential to life, and vital to the progress of civilizations. It is delightful to sip on a hot summer day or to watch falling gracefully into a fountain basin. However, water becomes an insidious foe when it decides to start pouring into your basement or collecting in sodden pools on your lawn. So, “which type of drain should I use?”

Drainage, therefore, is a constant concern in the Pacific Northwest landscape. There are various devices designed to direct water over and through the landscape. Sometimes the terms can get confusing, so today I’d like to clarify the difference between three of the most common water diversion mechanisms: trench drains vs. French drains vs. swales.

SURFACE VS. SUBSURFACE DRAINAGE

Before we begin, let’s explore some basic drainage concepts. There are two main types of drainage in the landscape: surface drainage and subsurface drainage. In any given landscape situation, it’s important to first assess what type you are dealing with.

As a general rule we use surface drainage to deal with rainwater, especially heavy rain. Typically in this situation you want the ability to drain large volumes of water away very quickly in order to avoid flooding and erosion, and to prevent it from going where it’s not wanted. A good example of a surface drainage mechanism is a ditch on the side of a highway. Swales, flumes and trench drains are also used in various situations to convey water over grass, concrete or other media.

In contrast, subsurface drainage deals with groundwater. This can be water that percolates down into the soil from above or bubbles up on your property. Here in the South you might have seen groundwater entering a basement that contains a nasty orange colored substance called bacterial iron. We normally use French drains to deal with that kind of saturation.

Now, let’s take a closer look at French drains, trench drains and swales, and the differences between them.

WHAT IS A FRENCH DRAIN?

Most people assume that the French drain was invented in France, but that’s not the case. It was actually named for its inventor, Henry Flagg French. French was an American who practically invented the fine art of farmland drainage, mainly to remove waste-contaminated water from feedlots and help prevent disease. He wrote a book called “Farm Drainage” in 1859 that literally became the basis of modern drainage.

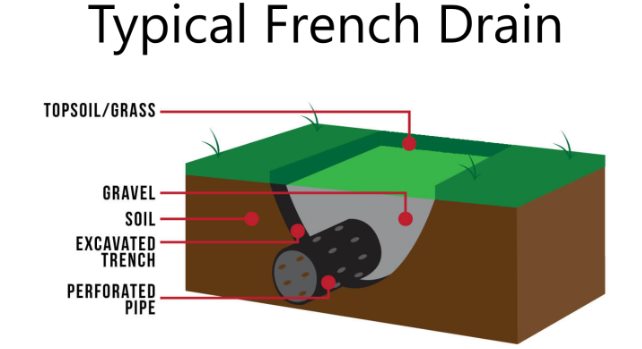

The French drain is a true subsurface structure meant to address water that saturates the soil. Water is insidious, and will always seek the path of least resistance. When water flows through soil it’s typically under a lot of hydrostatic pressure. Often there will be a harder layer of soil or even rock under the top layer of soil. In this case the hydrostatic force pushes the water both downward and transversely, which is why it’s so common for water to move sideways through a foundation.

When water comes to a foundation wall, it tends to seep through any chink or crack in the mortar. A French drain works to keep your basement dry by diverting water from the surrounding soil into an underground barrier trench containing a gravel bed. Water is driven there because the voids in the gravel make it easy for it to travel through, making the gravel bed the path of least resistance. The water then flows into perforated pipes at the bottom of the trench. From there it is eventually discharged to an outlet, such as a swale, storm sewer, irrigation cistern, or sump. The entire system has to be designed to accommodate the natural flow of water from higher ground to the lowest point.

FRENCH DRAIN SECRETS

I can’t mention French drains without bragging a bit about our methods, because we include a few extra features that most companies don’t:

- We include access points or cleanouts on the lines to facilitate maintenance and prolong the life of the system. Very important for routine maintenance of your drainage system.

- If we pick up downspouts along the way, we send that water to a separate pipe, so it doesn’t backflow into the drainage system.

- The most common problem with French drains is root intrusion; we use a filter fabric as a preventative measure to help keep roots out of the system.

- When installing a French drain under a driveway or road, we use heavy duty structural corrugated drain pipe, not the stuff from the big box stores which can collapse if a truck drives over it.

- We also bury our French drains at least 12”-18” deep to avoid collapse.

Does it add to the cost to do it this way? Well, it depends on how you look at it. When you consider the cost of re-doing a French drain—including all the excavation and disruption to the landscape—we think it’s well worth it to do it right the first time. So when you ask which type of drain should I use, I feel the key is to have a professional come out and look at your terrain and landscape and have them design a drain system that will hold up here in the Seattle, Pacific Northwest area.

FRENCH DRAINS VS. TRENCH DRAINS

There’s a lot of confusion between French drains and trench drains, because they sound so similar and because the French drain does incorporate a trench. However, unlike the French drain, the trench drain is a surface drainage structure.

A trench drain is a device designed to intercept and collect surface water over a long expanse. It is literally a trench with a grate on top. Trench drains are usually employed across a paved area to drain and direct water away from these surfaces. You see them a lot around commercial buildings like restaurants or loading docks to help keep the pavement in these areas dry and slip-free.

Even though a trench drain is embedded in the ground, it is technically a surface drainage mechanism designed to clear water away fast. Under the grate is typically a plastic box-shaped trench that acts as a hidden surface water conveyance. A trench drain can be heavy duty and wide, ranging down to the inch-wide microdrains you’ve probably seen in pool decks.

TRENCH DRAIN VS. SWALE

Like a trench drain, a swale is a surface water drainage device. However, it’s a lot more subtle in terms of its appearance in the landscape.

A swale is like a ditch but it’s broad and shallow, and usually covered or lined with turfgrass or other vegetation. The purpose is to slow and control the flow of water to prevent flooding, puddling, and erosion and/or avoid overwhelming the storm drain system. Any time we can spread water out we slow it down and it will percolate naturally into the soil. (This is one of the main differences between a swale and a ditch; ditches tend to be deeper and to concentrate the water flow which increases its speed and volatility.)

Swales are very handy when you don’t want your drainage system to be obvious. A typical swale has a parabolic profile, starting at one edge and gently flowing down and up. You can do one so broad and shallow that it looks like part of the sculpting of the landscape. For this reason swales are often used in residential or commercial settings where there are large expanses of turf. You can also use them in sustainable landscape applications for water conservation.